FMLA, ADA violations land employer in court

Employers must consider workplace accommodations

As part of his job, Charles worked a swing shift, rotating between days and nights. This schedule helped maintain employee morale and meet company demands.

A few years into job, Charles was diagnosed with depression, anorexia, and anxiety, and requested intermittent leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). The employer, however, put him on continuous leave. At the end of the FMLA leave, he was placed on short-term disability leave.

Schedule change controversy

Later that year, however, Charles provided letters from his health care providers stating that he would benefit from a consistent work schedule, as returning to a swing shift could directly affect his progress and future success. This was a request for an accommodation under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

A couple months later, the employer offered to put Charles on a consistent schedule of only day shift or only night shift for a period of 30 days, with no possibility of reevaluation after that. Charles declined the offer, as he wanted to follow his doctor’s orders.

He tried to talk to his employer about it for the next month. The employer refused to consider a permanent consistent schedule and delayed any practical discussion about accommodations. That left Charles with the options of going back to a swing shift, quitting, or being fired. He resigned and found a new job.

Case lands in court

Charles sued his former employer, arguing that the company violated his FMLA rights and failed to accommodate his disability.

He also argued that the company made him take continuous FMLA leave instead of his requested intermittent leave. The court agreed that this could be seen as interference or retaliation.

As for the accommodation claim, the employer argued that Charles caused the breakdown in the interactive process. The court didn’t buy the employer’s argument, and found that the employer’s refusal to consider any accommodation beyond the 30-day period despite Charles’ repeated attempts to discuss it was the main cause of the breakdown. The company also did not show that an accommodation beyond the 30-day period would have been unreasonable or unduly burdensome.

Lessons for all employers

Employers that overlook their obligations to discuss workplace accommodations under the ADA after FMLA leave ends risk having to defend their actions in court. This costs employers valuable resources, such as time and money, and brandishes their public image.

It likely would have been easier had this employer simply let the employee work one shift. The employer should also have allowed the intermittent FMLA leave.

Cooke v. Carpenter Technology Corporation, 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, No. 20-14606, December 16, 2022.

Key to Remember: Employers that overlook their obligations to discuss workplace accommodations under the ADA after FMLA leave ends risk having to spend resources defending their actions in court.

This article was written by Darlene M. Clabault, SHRM-CP, PHR, CLMS, of J. J. Keller & Associates, Inc. The content of these news items, in whole or in part, MAY NOT be copied into any other uses without consulting the originator of the content.

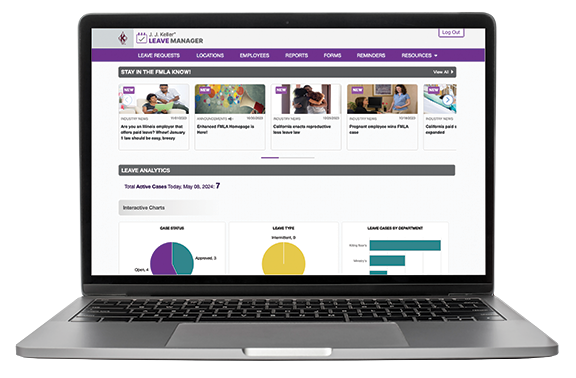

The J. J. Keller LEAVE MANAGER service is your business resource for tracking employee leave and ensuring compliance with the latest Federal and State FMLA and leave requirements.